- How shall we portray Iluvatar?

- How shall we portray the Valar?

- How shall we deal with songs/magic?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Episode 0-1

- Thread starter Trish Lambert

- Start date

David Russell Mosley

New Member

This might be controversial, but what if we didn't depict Iluvatar? If we stick with the general idea that Tolkien is basing Iluvatar on the Judeo-Christian God, then in his essence Iluvatar has no visible form. He can, of course, appear in a form, and perhaps he would even for the Valar (who, again if we somewhat correlate them to angels, are pure intellects without corporeal bodies). However, one cannot depict pure intellects, let alone pure divinity. So, I suggest this: For Iluvatar, pre-creation of the Valar, we have pure white. Then as the music begins (I'll deal with that in a moment), colours begin to appear. Insofar as we can, each colour ought to somewhat correspond to what each named Valar will come to represent. Manwe would be flashes of sky blue and white, Yavanna greens and browns, Ulmo sea-grean, blue, and white, Melkor red and black, Aüle greys, but also emerald, ruby, etc. The idea behind this, especially if we go for a pure white to represent Iluvatar, is that if each of the Valar is represented by colour, then this would give visual depiction of that notion that each knew the part of Iluvatar's mind from whence they come since colour is a fragment of white (when dealing with light and not pigment). Absolutely key, if we're going to keep the theology consistent here, would be for all things to appear on the background of the white, including Arda once it is created, for in Christian theology, creation is not the creation of God and another thing, but a suspension from God of the things created, emphasising that God is the only true existent thing and that all other "things" have existence or thingness by participation in God. It isn't necessary, of course, to believe this (I happen to), but I think it is necessary for a faithful depiction of Tolkien's words and ideas.

As for the music (which I will distinguish from magic for now) of creation, I see a few options. We could go the Fantasia route and use orchestral music, either originally composed or classical pieces, with each Valar representing a different instrument/section. Using classical pieces, however, would be difficult when we arrive at Melkor's discord and the harmony Iluvatar brings out of it. I like the idea of the music being instrumental rather than vocal, for the Valar specifically, because it would add to the difference between the Valar and the children of Iluvatar. However, eventually, they would need to speak, unless we're going to go full Fantasia, in order to be comprehensible to the audience. So perhaps a blend of human voices and instruments, each Valar "performing" the same notes with both. For the elves, perhaps we could see them singing and playing instruments––Orfeo and his harp come to mind––in a kind of participating in the instrumental-vocalities of the Valar, who themselves are participating in Iluvatar's chosen method of expression. In other words, not unlike Thorin and Co. each elf, or at least some, often carries with him or her a particular instrument for the purpose of "performing magic" which is seems a bit too wizardy, but is at the same time different since Tolkien's wizards seem to perform magic in a different way.

The question for the elves, because I think it would be different and fairly simple for the Valar, is how to depict what's going on when they sing/play? For the Valar, since their music is the means of creating a vision of creation, the music would create the image of the cosmos in front of them, devoid of sun and moon if we want to use the story of their creation for a future episode. Since the elves won't be performing any "magic" in the first episodes we can leave it aside. That said, I think it important to connect elvish magic, since it tends to happen by song, to the singing of the Valar in order to ensure we see them as related things, which I think they are.

As for the music (which I will distinguish from magic for now) of creation, I see a few options. We could go the Fantasia route and use orchestral music, either originally composed or classical pieces, with each Valar representing a different instrument/section. Using classical pieces, however, would be difficult when we arrive at Melkor's discord and the harmony Iluvatar brings out of it. I like the idea of the music being instrumental rather than vocal, for the Valar specifically, because it would add to the difference between the Valar and the children of Iluvatar. However, eventually, they would need to speak, unless we're going to go full Fantasia, in order to be comprehensible to the audience. So perhaps a blend of human voices and instruments, each Valar "performing" the same notes with both. For the elves, perhaps we could see them singing and playing instruments––Orfeo and his harp come to mind––in a kind of participating in the instrumental-vocalities of the Valar, who themselves are participating in Iluvatar's chosen method of expression. In other words, not unlike Thorin and Co. each elf, or at least some, often carries with him or her a particular instrument for the purpose of "performing magic" which is seems a bit too wizardy, but is at the same time different since Tolkien's wizards seem to perform magic in a different way.

The question for the elves, because I think it would be different and fairly simple for the Valar, is how to depict what's going on when they sing/play? For the Valar, since their music is the means of creating a vision of creation, the music would create the image of the cosmos in front of them, devoid of sun and moon if we want to use the story of their creation for a future episode. Since the elves won't be performing any "magic" in the first episodes we can leave it aside. That said, I think it important to connect elvish magic, since it tends to happen by song, to the singing of the Valar in order to ensure we see them as related things, which I think they are.

Nelson Holmes

New Member

The Ainlulindalë, I think, can be divided into two parts. First, there is the Music of the Ainur, which culminates in the discord of Melkor and Ilúvatar's final chord (higher than the firmament, deeper than the abyss, etc.). Then we move into the second part, which involves Ilúvatar speaking to the Ainur (this is important) and showing them their creation.

For the purposes of telling a story that is visually coherent, it makes sense that during the Music of the Ainur Ilúvatar and the Ainur could be depicted as colors and abstract shapes. That sort of works with the whole idea of creation - something from nothing. You start with colors and shapes and it gradually coalesces into Arda as we see it. However, once we enter Part 2, where Ilúvatar begins to speak and address the Ainur - once dialogue begins - I think it's necessary that we see the Ainur and possibly even Ilúvatar "embodied" in human form. That is to say, their interactions should not be depicted as disembodied, abstract forms talking to each other.

Now, I realize that the Ainur only become "embodied" (in a sense) when they descend into Arda. However, for the drama of the Ainulindalë (and it is a drama, as well as a creation myth) to unfold in a meaningful, coherent, and watchable way, I think at least part of it needs to involve Ilúvatar and the Gods sitting around and actually talking to each other much like people would. Picture Ilúvatar on his throne, making his speech at the conclusion of the music, addressing thousands of Ainur, and singling out Melkor, who then turns away in shame. This also gives viewers the opportunity to not only see the drama unfold, but also put names with faces - that's Ulmo standing over there, that's Manwë sitting close to Ilúvatar's throne, that's Melkor standing up front, challenging Ilúvatar's music with his own.

The overall point I'm making is that a colorful, abstract, Fantasia-esque creation sequence works fine up to a point, but I firmly believe that at some point the drama needs to start unfolding with actual bodies in the Timeless Halls of Ilúvatar.

For the purposes of telling a story that is visually coherent, it makes sense that during the Music of the Ainur Ilúvatar and the Ainur could be depicted as colors and abstract shapes. That sort of works with the whole idea of creation - something from nothing. You start with colors and shapes and it gradually coalesces into Arda as we see it. However, once we enter Part 2, where Ilúvatar begins to speak and address the Ainur - once dialogue begins - I think it's necessary that we see the Ainur and possibly even Ilúvatar "embodied" in human form. That is to say, their interactions should not be depicted as disembodied, abstract forms talking to each other.

Now, I realize that the Ainur only become "embodied" (in a sense) when they descend into Arda. However, for the drama of the Ainulindalë (and it is a drama, as well as a creation myth) to unfold in a meaningful, coherent, and watchable way, I think at least part of it needs to involve Ilúvatar and the Gods sitting around and actually talking to each other much like people would. Picture Ilúvatar on his throne, making his speech at the conclusion of the music, addressing thousands of Ainur, and singling out Melkor, who then turns away in shame. This also gives viewers the opportunity to not only see the drama unfold, but also put names with faces - that's Ulmo standing over there, that's Manwë sitting close to Ilúvatar's throne, that's Melkor standing up front, challenging Ilúvatar's music with his own.

The overall point I'm making is that a colorful, abstract, Fantasia-esque creation sequence works fine up to a point, but I firmly believe that at some point the drama needs to start unfolding with actual bodies in the Timeless Halls of Ilúvatar.

Bre

Active Member

For now I'm only to tackle a portion of the above questions, as I plan on making some sketches to help me discuss more specifically how I think these characters should appear on-screen. For now I'm mainly going to focus on the mode through which the Ainulindalë should be told, as it is where my mind starts when first thinking about the above questions.

-------

Dieties and angels have been depicted in art for thousands of years through a vast array of different styles, so the issue isn't so much if Illuvatar and the Valar should be visually depicted but if either should be depicted in more traditional fashions based on Tolkien's own intentions and how the text represents them visually.

By the time the elves arrive the Valar have taken on physical forms, and these forms are visually described by Tolkien; it's primarily during the Ainulindalë that how they should be conveyed on-screen becomes more controversial because at that stage all beings are abstract and primarily conveyed through other senses like sound rather visually.

However, Illuvatar is never physically depicted, but is represented only through sound and impressions (the only time the text gets close to anything visual with Illuvatar is when it states that he smiles, but this debatably could be conveyed through sound or abstract shapes and light instead of something as concrete as a character design).

Since the Ainulindalë is a story conveyed by song, I see no reason why that shouldn't be the same in a film. The appropriate narrative style to communicate this is an orchestrated piece of music supported by a visual montague like the many shorts of Fantasia and Fantasia 2000.

Whenever I mention this Fantasia idea, I am almost immediately asked if I mean something like Fantasia's 'Rite of Spring,' which depicts the creation and early evolution of the Earth.

However, the visuals in that are still fairly concrete and anything similar to it in a Silmarillion film would only apply after the Valar descend into Arda to shape it. And even with that said I prefer the visuals of Fantasia 2000's 'Firebird' and some of the concepts present in 'Night On Bald Mountain' for the Shaping of Arda. All visuals prior to this moment, would mostly be changing color and intensity of light to convey the drama at the time of the making of the music (i.e. the discord of Melkor).

The closest Disney ever gets to what the Ainulindale should be is in Fantasia 2000's 'Symphony No. 5 in C minor. Allegro con brio', which even has an similar plot.

-----

P.S. I wanted to also cite some UPA style animation shorts as examples of orchestrated music couple with abstract animated sequences, but I'm having trouble finding the ones that would be more suited to this discussion. Basically these shorts just depicted musical notes and instruments changing shape and color based on musical ques. I managed to find some online examples of Disney employing the UPA style, but not quite to the same effect.

P.P.S. Also if it isn't clear by now, while I'm in the camp of having the entirety of The Silmarillion animated, I think the Ainulindalë should be animated regardless of whether or not the other stories are live-action.

-------

Dieties and angels have been depicted in art for thousands of years through a vast array of different styles, so the issue isn't so much if Illuvatar and the Valar should be visually depicted but if either should be depicted in more traditional fashions based on Tolkien's own intentions and how the text represents them visually.

By the time the elves arrive the Valar have taken on physical forms, and these forms are visually described by Tolkien; it's primarily during the Ainulindalë that how they should be conveyed on-screen becomes more controversial because at that stage all beings are abstract and primarily conveyed through other senses like sound rather visually.

However, Illuvatar is never physically depicted, but is represented only through sound and impressions (the only time the text gets close to anything visual with Illuvatar is when it states that he smiles, but this debatably could be conveyed through sound or abstract shapes and light instead of something as concrete as a character design).

Since the Ainulindalë is a story conveyed by song, I see no reason why that shouldn't be the same in a film. The appropriate narrative style to communicate this is an orchestrated piece of music supported by a visual montague like the many shorts of Fantasia and Fantasia 2000.

Whenever I mention this Fantasia idea, I am almost immediately asked if I mean something like Fantasia's 'Rite of Spring,' which depicts the creation and early evolution of the Earth.

However, the visuals in that are still fairly concrete and anything similar to it in a Silmarillion film would only apply after the Valar descend into Arda to shape it. And even with that said I prefer the visuals of Fantasia 2000's 'Firebird' and some of the concepts present in 'Night On Bald Mountain' for the Shaping of Arda. All visuals prior to this moment, would mostly be changing color and intensity of light to convey the drama at the time of the making of the music (i.e. the discord of Melkor).

The closest Disney ever gets to what the Ainulindale should be is in Fantasia 2000's 'Symphony No. 5 in C minor. Allegro con brio', which even has an similar plot.

-----

P.S. I wanted to also cite some UPA style animation shorts as examples of orchestrated music couple with abstract animated sequences, but I'm having trouble finding the ones that would be more suited to this discussion. Basically these shorts just depicted musical notes and instruments changing shape and color based on musical ques. I managed to find some online examples of Disney employing the UPA style, but not quite to the same effect.

P.P.S. Also if it isn't clear by now, while I'm in the camp of having the entirety of The Silmarillion animated, I think the Ainulindalë should be animated regardless of whether or not the other stories are live-action.

NicoleHobbitday

New Member

I think the Ainulindalë is one of the primary examples of why people consider The Silmarillion to be "un-filmable," even more so than The Lord of the Rings. It would take a very subtle and cautious hand to portray the abstract visual concepts in not just the Ainulindalë, but the entirety of The Silmarillion. Going after The Silmarillion as an episodic series has a lot of advantages, mostly because you won't have to condense things as much, and you don't necessarily have to constrict things to a structured story arch, the way a feature film would benefit from.

But you're still going to have to make things concise. You're still going to have to, as they say, "kill your babies" from time to time and condense things. You also want it to be accessible to a non-reading audience (I think, at least, as the Peter Jackson films already have an audience base and it would be a shame to exclude non-readers from experiencing Tolkien. Not to mention, no studio would produce something that was only able to be enjoyed by such a small percentage of people as Silmarillion readers.)

Personally I've always envisioned the backstory of the Valar and the creation of Arda as a prologue (maybe with a handy dandy narration from Galadriel, for old time's sake?). A feature film version of The Silmarillion has been a dream of mine since I first read the book in high school. I actually have a screenplay draft in the works, and the way I have it set up is a series of cosmic visuals, with light and sound emerging from the Void in time with a narration. It simply describes that "before the world there was Eru, Illuvatar, the One" and he filled the Void with music. In his music was the blueprint of creation, and his "agents" the Valar were tasked with bringing this music to life.

In order for this to not look like crap, it would take a very visually careful director, and musical composer. I think subtle orchestral music can help literally represent the Valar, along with visuals of light. Like stars. This light could descend to a barren, shapeless earth and take their physical forms. I imagine sort of like the way Apparition is shown in the Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix film, for those of you who know what I'm talking about.

From then on the Valar would be represented by respective actors. I don't think there's any need to show Illuvatar, nor is it necessary to.

But you're still going to have to make things concise. You're still going to have to, as they say, "kill your babies" from time to time and condense things. You also want it to be accessible to a non-reading audience (I think, at least, as the Peter Jackson films already have an audience base and it would be a shame to exclude non-readers from experiencing Tolkien. Not to mention, no studio would produce something that was only able to be enjoyed by such a small percentage of people as Silmarillion readers.)

Personally I've always envisioned the backstory of the Valar and the creation of Arda as a prologue (maybe with a handy dandy narration from Galadriel, for old time's sake?). A feature film version of The Silmarillion has been a dream of mine since I first read the book in high school. I actually have a screenplay draft in the works, and the way I have it set up is a series of cosmic visuals, with light and sound emerging from the Void in time with a narration. It simply describes that "before the world there was Eru, Illuvatar, the One" and he filled the Void with music. In his music was the blueprint of creation, and his "agents" the Valar were tasked with bringing this music to life.

In order for this to not look like crap, it would take a very visually careful director, and musical composer. I think subtle orchestral music can help literally represent the Valar, along with visuals of light. Like stars. This light could descend to a barren, shapeless earth and take their physical forms. I imagine sort of like the way Apparition is shown in the Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix film, for those of you who know what I'm talking about.

From then on the Valar would be represented by respective actors. I don't think there's any need to show Illuvatar, nor is it necessary to.

Halstein

Active Member

Hi.

Having just re-read the Ainulindalë, I think it might be go rather quickly to anthropomorphic Valar/Illuvatar. Not necessarily human actors, as CGI-characters might be a way to go. Illuvatar is described as smiling, and looking stern, as well as raising his hand (when Melkor gets ideas), so I think showing him makes sense. Agree with starting out with colors like David suggest, but I think the music bit should be rather short, before going to dialog. Illuvatar should in my opinion be made up of white light. The Valar should be made up of appropriate colors, until they enter "proto-Arda". Then they should take on more ordinary forms.

When it come to the music, I would give the different Valar their own leitmotiv, and the music also should contain some recognizable themes. Tolkien writes that in addition to sounds like instruments, there are parts with chorus. I would add chorus to the orchestral music, and would not exclude non-orchestral instruments.

Magic should be songs in my opinion. The words are what one want to accomplish, and the tune is a variation on a theme from the song of the Valar.

Having just re-read the Ainulindalë, I think it might be go rather quickly to anthropomorphic Valar/Illuvatar. Not necessarily human actors, as CGI-characters might be a way to go. Illuvatar is described as smiling, and looking stern, as well as raising his hand (when Melkor gets ideas), so I think showing him makes sense. Agree with starting out with colors like David suggest, but I think the music bit should be rather short, before going to dialog. Illuvatar should in my opinion be made up of white light. The Valar should be made up of appropriate colors, until they enter "proto-Arda". Then they should take on more ordinary forms.

When it come to the music, I would give the different Valar their own leitmotiv, and the music also should contain some recognizable themes. Tolkien writes that in addition to sounds like instruments, there are parts with chorus. I would add chorus to the orchestral music, and would not exclude non-orchestral instruments.

Magic should be songs in my opinion. The words are what one want to accomplish, and the tune is a variation on a theme from the song of the Valar.

DMae

New Member

Every time I reread the Ainulindalë I think of Morgan Freeman's deep, resonant voice as Illuvatar. I hear it in my ears as I read.

Visually, I tend to see the Valar as animated characters (agreeing with Bre on this part) who move various shapes and colors to create their music. In my ears, as I read, I usually hear various classical scores. The funny thing about this is that every time I reread this section, I don't hear the same music. Once I heard, in my mind, some Sheryl Crow.... The shape of the words on the paper tend to lend themselves to various sounds and colors to me. Does this happen to anyone else?

So, I guess for me the Valar singing Arda into being would consist of a classical type of score, with the Valar being represented by colors in discrete patterns that would lend themselves to the end product of each Vala's creation.

Magic? What magic? I thought this was all fact.

Visually, I tend to see the Valar as animated characters (agreeing with Bre on this part) who move various shapes and colors to create their music. In my ears, as I read, I usually hear various classical scores. The funny thing about this is that every time I reread this section, I don't hear the same music. Once I heard, in my mind, some Sheryl Crow.... The shape of the words on the paper tend to lend themselves to various sounds and colors to me. Does this happen to anyone else?

So, I guess for me the Valar singing Arda into being would consist of a classical type of score, with the Valar being represented by colors in discrete patterns that would lend themselves to the end product of each Vala's creation.

Magic? What magic? I thought this was all fact.

S

Sep

Guest

I agree with the others that say the Ainulindale needs to be animated. I think we could take Evan Palmer's take on it as a good inspiration for what the visuals might look like. I think that none of the Ainur or Iluvatar would actually have dialog - it would all be narration by someone in the frame narrative.

For music, I think that we should do something like what Howard Shore did in the LotR trilogy, with an extensive set of leitmotifs and themes, mirroring the Music of the Ainur.

For music, I think that we should do something like what Howard Shore did in the LotR trilogy, with an extensive set of leitmotifs and themes, mirroring the Music of the Ainur.

G.WilsonU2

New Member

I agree with the suggestions and ideas before mine. I like the idea of correlating the music ,Fantasia style ,to the visuals. However, I think it would be nice if we could compose our own "interchanging melodies". These melodies and leitmotifs could be used again later on in the series to portray characters and themes.

With the visuals ,I like the idea of the colors associated with each character. Illuvatar being white and the Valar all being refractions of his light sounds like a great idea. However , I don't think the Valar would be able to stay as splashes of color throughout the whole singing. They are interactive characters so we will need to be able to associate a face with a name. Maybe the colors could change into humanoid shapes at the moment when the music stops being separate melodies and begins to harmonize one with another. (This may be something to discuss further because technically the Valar didn't take on physical forms until they entered Arda. We would have to make it visually clear that their pre-Arda shape's are spirits)

I personally like the idea of animation over CGI or live action. CGI looks a little off in the same way that robots look off. When it comes to live action, I think it would be hard to do justice to such an important and memorable scene in Tolkien's work with real actors. It might also take away from the deep mythological feel that that text has.

ADDITIONAL NOTE : My apologies I must not have specified. When I'm talking about rendering it as animation, I'm specifically referring to the Ainulindale. I think it would be a great idea to do the rest of the series in live action. Animation does give a different feel. But I think thats okay when it comes to the Ainulindale. It's supposed to have a different, mythical feel.

With the visuals ,I like the idea of the colors associated with each character. Illuvatar being white and the Valar all being refractions of his light sounds like a great idea. However , I don't think the Valar would be able to stay as splashes of color throughout the whole singing. They are interactive characters so we will need to be able to associate a face with a name. Maybe the colors could change into humanoid shapes at the moment when the music stops being separate melodies and begins to harmonize one with another. (This may be something to discuss further because technically the Valar didn't take on physical forms until they entered Arda. We would have to make it visually clear that their pre-Arda shape's are spirits)

I personally like the idea of animation over CGI or live action. CGI looks a little off in the same way that robots look off. When it comes to live action, I think it would be hard to do justice to such an important and memorable scene in Tolkien's work with real actors. It might also take away from the deep mythological feel that that text has.

ADDITIONAL NOTE : My apologies I must not have specified. When I'm talking about rendering it as animation, I'm specifically referring to the Ainulindale. I think it would be a great idea to do the rest of the series in live action. Animation does give a different feel. But I think thats okay when it comes to the Ainulindale. It's supposed to have a different, mythical feel.

Last edited:

Nelson Holmes

New Member

I disagree with all proposals that The Silmarillion be animated, for three primary reasons.

1. It would certainly work from a practical standpoint, but I think it robs us of some great challenges. It feels like a shortcut that allows us to gloss over things that would be "too difficult" to portray onscreen via live action, VFX , or CGI. Animation gives us a way to skirt around some of the real difficulties of adapting The Silmarillion for the screen and making it believable. The beauty of animation is that it doesn't have to be believable, but the tragedy therein is that it cannot, by its very nature, be believable (but more on that later). My primary point here is that trying to envision The Silmarillion as a live action series is hard, perhaps even impossible in some places, but such is the nature of adaptation. It is our job, as the adapters, to figure out how to make it work. Animation might relieve us of a few of those hard choices, but that's half the fun of working out a good adaptation!

2. I see an argument forming centered around the idea that animation will allow us to be more faithful to the text. I disagree. Tolkien envisioned a secondary world with the same vivid reality as our own. He spent his lifetime creating (or subcreating) a universe that the rest of us could fully immerse ourselves in and, in a sense, believe in. It had many fantastical elements but in its substance it was like the primary world; it acted like the primary world, and it looked like the primary world. Animation might give Tolkien's world a greater mythological feel, but it robs us of the reality that was invested in every fiber of his sub-creation, not only the visual reality but the pervasive physical reality that grounded so much of his work.

3. Finally, a viewer will invest in a live action story in a way that they simply cannot with animation. If someone sits down and watches an animated series, they are aware at all times that they are watching something that is not real, that it cannot be real. Sitting down to watch a live action movie we are, of course, also aware that it is not real. But its visual medium resonates more closely with reality and allows for greater immersion into the secondary world of that film. It is "more real". From a pure storytelling perspective animation and live action can be equals, but from a visual perspective live action will always capture the viewer in a way animation cannot simply by the nature of the the medium.

Animation vs. live action seems to be a big important debate that's developing. The outcome will have a huge, irreversible impact on the nature of the Silm Film Project. There will come a time very soon when we have to pick one of the two and stick with it. I hope we will get a chance to have this discussion in one of the Season 0 episodes and come to a consensus: animation or live action?

Additional Note: The obvious compromise here is to animate some things but not others (e.g., animate the Ainulindalë but make the rest live action). I am equally opposed to this, for the simple reason that changing the medium, or worse intermingling animation and live action, is jarring and visually unappealing. Transition between and mingling of CGI and live action works because CGI can be made to look like the real world. Animation, in the form that it is being described, cannot. I just wanted to clarify the scope of my opposition to animation concerning the project.

1. It would certainly work from a practical standpoint, but I think it robs us of some great challenges. It feels like a shortcut that allows us to gloss over things that would be "too difficult" to portray onscreen via live action, VFX , or CGI. Animation gives us a way to skirt around some of the real difficulties of adapting The Silmarillion for the screen and making it believable. The beauty of animation is that it doesn't have to be believable, but the tragedy therein is that it cannot, by its very nature, be believable (but more on that later). My primary point here is that trying to envision The Silmarillion as a live action series is hard, perhaps even impossible in some places, but such is the nature of adaptation. It is our job, as the adapters, to figure out how to make it work. Animation might relieve us of a few of those hard choices, but that's half the fun of working out a good adaptation!

2. I see an argument forming centered around the idea that animation will allow us to be more faithful to the text. I disagree. Tolkien envisioned a secondary world with the same vivid reality as our own. He spent his lifetime creating (or subcreating) a universe that the rest of us could fully immerse ourselves in and, in a sense, believe in. It had many fantastical elements but in its substance it was like the primary world; it acted like the primary world, and it looked like the primary world. Animation might give Tolkien's world a greater mythological feel, but it robs us of the reality that was invested in every fiber of his sub-creation, not only the visual reality but the pervasive physical reality that grounded so much of his work.

3. Finally, a viewer will invest in a live action story in a way that they simply cannot with animation. If someone sits down and watches an animated series, they are aware at all times that they are watching something that is not real, that it cannot be real. Sitting down to watch a live action movie we are, of course, also aware that it is not real. But its visual medium resonates more closely with reality and allows for greater immersion into the secondary world of that film. It is "more real". From a pure storytelling perspective animation and live action can be equals, but from a visual perspective live action will always capture the viewer in a way animation cannot simply by the nature of the the medium.

Animation vs. live action seems to be a big important debate that's developing. The outcome will have a huge, irreversible impact on the nature of the Silm Film Project. There will come a time very soon when we have to pick one of the two and stick with it. I hope we will get a chance to have this discussion in one of the Season 0 episodes and come to a consensus: animation or live action?

Additional Note: The obvious compromise here is to animate some things but not others (e.g., animate the Ainulindalë but make the rest live action). I am equally opposed to this, for the simple reason that changing the medium, or worse intermingling animation and live action, is jarring and visually unappealing. Transition between and mingling of CGI and live action works because CGI can be made to look like the real world. Animation, in the form that it is being described, cannot. I just wanted to clarify the scope of my opposition to animation concerning the project.

Last edited:

Tom Hillman

New Member

When the question of how and whether to portray Iluvatar came up in the podcast, I couldn't help thinking of Odysseus' Scar, the first chapter of Erich Auerbach's Mimesis, where he does such a terrific job of distinguishing between the two fundamental and fundamentally different ways of representing reality in Western Literature. I am going to provide a fairly lengthy quote from that chapter below because I think it is apposite to our discussion here.

I agree with Breanna that there is a long tradition in art of representing God, gods, and other lesser supernatural beings. And once the Ainur put on flesh and enter Arda that tradition, and Tolkien's awareness of it, should certainly be embraced. But Tolkien also makes a clear distinction between the Ainur before incarnation and after it, which I think we should also strive to embrace, though how we would do is a different and difficult question. But we're a pretty clever and talented bunch here, so I imagine we'll come up with something. As for Iluvatar, I think we should leave him unrepresented visually, as Tolkien does even after the creation of Arda and the incarnation of the Valar. Even when Iluvatar comes to Aule after Aule has made the dwarves, he does not come to him in a bodily guise. Aule knows he is there and hears his voice. That is all. Even in The Converse of Manwe and Eru (HoME 10.36162) we get a similar, but now two sided bodiless conversation on a blank stage. "Manwe spoke to Eru, saying...Eru answered...Manwe asked....Eru answered...."

So here's the quote. I think you'll see the connection.

I agree with Breanna that there is a long tradition in art of representing God, gods, and other lesser supernatural beings. And once the Ainur put on flesh and enter Arda that tradition, and Tolkien's awareness of it, should certainly be embraced. But Tolkien also makes a clear distinction between the Ainur before incarnation and after it, which I think we should also strive to embrace, though how we would do is a different and difficult question. But we're a pretty clever and talented bunch here, so I imagine we'll come up with something. As for Iluvatar, I think we should leave him unrepresented visually, as Tolkien does even after the creation of Arda and the incarnation of the Valar. Even when Iluvatar comes to Aule after Aule has made the dwarves, he does not come to him in a bodily guise. Aule knows he is there and hears his voice. That is all. Even in The Converse of Manwe and Eru (HoME 10.36162) we get a similar, but now two sided bodiless conversation on a blank stage. "Manwe spoke to Eru, saying...Eru answered...Manwe asked....Eru answered...."

So here's the quote. I think you'll see the connection.

'The genius of the Homeric style becomes even more apparent when it is compared with an equally ancient and equally epic style from a different world of forms. I shall attempt this comparison with the account of the sacrifice of Isaac, a homogeneous narrative produced by the so-called Elohist. The King James version translates the opening as follows (Genesis 22: 1): “And it came to pass after these things, that God did tempt Abraham, and said to him, Abraham! and he said, Behold, here I am.” Even this opening startles us when we come to it from Homer. Where are the two speakers? We are not told. The reader, however, knows that they are not normally to be found together in one place on earth, that one of them, God, in order to speak to Abraham, must come from somewhere, must enter the earthly realm from some unknown heights or depths. Whence does he come, whence does he call to Abraham? We are not told. He does not come, like Zeus or Poseidon, from the Aethiopians, where he has been enjoying a sacrificial feast. Nor are we told anything of his reasons for tempting Abraham so terribly. He has not, like Zeus, discussed them in set speeches with other gods gathered in council; nor have the deliberations in his own heart been presented to us; unexpected and mysterious, he enters the scene from some unknown height or depth and calls: Abraham! It will at once be said that this is to be explained by the particular concept of God which the Jews held and which was wholly different from that of the Greeks. True enough—but this constitutes no objection. For how is the Jewish concept of God to be explained? Even their earlier God of the desert was not fixed in form and content, and was alone; his lack of form, his lack of local habitation, his singleness, was in the end not only maintained but developed even further in competition with the comparatively far more manifest gods of the surrounding Near Eastern world. The concept of God held by the Jews is less a cause than a symptom of their manner of comprehending and representing things.

'This becomes still clearer if we now turn to the other person in the dialogue, to Abraham. Where is he? We do not know. He says, indeed: Here I am—but the Hebrew word means only something like “behold me,” and in any case is not meant to indicate the actual place where Abraham is, but a moral position in respect to God, who has called to him—Here am I awaiting thy command. Where he is actually, whether in Beersheba or elsewhere, whether indoors or in the open air, is not stated; it does not interest the narrator, the reader is not informed; and what Abraham was doing when God called to him is left in the same obscurity. To realize the difference, consider Hermes’ visit to Calypso, for example, where command, journey, arrival and reception of the visitor, situation and occupation of the person visited, are set forth in many verses; and even on occasions when gods appear suddenly and briefly, whether to help one of their favorites or to deceive or destroy some mortal whom they hate, their bodily forms, and usually the manner of their coming and going, are given in detail. Here, however, God appears without bodily form (yet he “appears”), coming from some unspecified place—we only hear his voice, and that utters nothing but a name, a name without an adjective, without a descriptive epithet for the person spoken to, such as is the rule in every Homeric address; and of Abraham too nothing is made perceptible except the words in which he answers God: Hinne-ni, Behold me here—with which, to be sure, a most touching gesture expressive of obedience and readiness is suggested, but it is left to the reader to visualize it. Moreover the two speakers are not on the same level: if we conceive of Abraham in the foreground, where it might be possible to picture him as prostrate or kneeling or bowing with outspread arms or gazing upward, God is not there too: Abraham’s words and gestures are directed toward the depths of the picture or upward, but in any case the undetermined, dark place from which the voice comes to him is not in the foreground.

'After this opening, God gives his command, and the story itself begins: everyone knows it; it unrolls with no episodes in a few independent sentences whose syntactical connection is of the most rudimentary sort. In this atmosphere it is unthinkable that an implement, a landscape through which the travelers passed, the servingmen, or the ass, should be described, that their origin or descent or material or appearance or usefulness should be set forth in terms of praise; they do not even admit an adjective: they are serving-men, ass, wood, and knife, and nothing else, without an epithet; they are there to serve the end which God has commanded; what in other respects they were, are, or will be, remains in darkness. A journey is made, because God has designated the place where the sacrifice is to be performed; but we are told nothing about the journey except that it took three days, and even that we are told in a mysterious way: Abraham and his followers rose “early in the morning” and “went unto” the place of which God had told him; on the third day he lifted up his eyes and saw the place from afar. That gesture is the only gesture, is indeed the only occurrence during the whole journey, of which we are told; and though its motivation lies in the fact that the place is elevated, its uniqueness still heightens the impression that the journey took place through a vacuum; it is as if, while he traveled on, Abraham had looked neither to the right nor to the left, had suppressed any sign of life in his followers and himself save only their footfalls.

'Thus the journey is like a silent progress through the indeterminate and the contingent, a holding of the breath, a process which has no present, which is inserted, like a blank duration, between what has passed and what lies ahead, and which yet is measured: three days! Three such days positively demand the symbolic interpretation which they later received. They began “early in the morning.” But at what time on the third day did Abraham lift up his eyes and see his goal? The text says nothing on the subject. Obviously not “late in the evening,” for it seems that there was still time enough to climb the mountain and make the sacrifice. So “early in the morning” is given, not as an indication of time, but for the sake of its ethical significance; it is intended to express the resolution, the promptness, the punctual obedience of the sorely tried Abraham. Bitter to him is the early morning in which he saddles his ass, calls his serving-men and his son Isaac, and sets out; but he obeys, he walks on until the third day, then lifts up his eyes and sees the place. Whence he comes, we do not know, but the goal is clearly stated: Jeruel in the land of Moriah. V/hat place this is meant to indicate is not clear—”Moriah” especially may be a later correction of some other word. But in any case the goal was given, and in any case it is a matter of some sacred spot which was to receive a particular consecration by being connected with Abraham's sacrifice. Just as little as “early in the morning” serves as a temporal indication does “Jeruel in the land of Moriah” serve as a geographical indication; and in both cases alike, the complementary indication is not given, for we know as little of the hour at which Abraham lifted up his eyes as we do of the place from which he set forth—Jeruel is significant not so much as the goal of an earthly journey, in its geographical relation to other places, as through its special election, through its relation to God, who designated it as the scene of the act, and therefore it must be named.'

I apologize for the length of this quote, but to me at least it does a good job of illustrating where Tolkien is also coming from in The Ainulindale and elsewhere when it comes to the "appearance" of Eru on stage in the story, and gives us something to think about as we move forward with the question of how to portray Eru and the Valar.

'This becomes still clearer if we now turn to the other person in the dialogue, to Abraham. Where is he? We do not know. He says, indeed: Here I am—but the Hebrew word means only something like “behold me,” and in any case is not meant to indicate the actual place where Abraham is, but a moral position in respect to God, who has called to him—Here am I awaiting thy command. Where he is actually, whether in Beersheba or elsewhere, whether indoors or in the open air, is not stated; it does not interest the narrator, the reader is not informed; and what Abraham was doing when God called to him is left in the same obscurity. To realize the difference, consider Hermes’ visit to Calypso, for example, where command, journey, arrival and reception of the visitor, situation and occupation of the person visited, are set forth in many verses; and even on occasions when gods appear suddenly and briefly, whether to help one of their favorites or to deceive or destroy some mortal whom they hate, their bodily forms, and usually the manner of their coming and going, are given in detail. Here, however, God appears without bodily form (yet he “appears”), coming from some unspecified place—we only hear his voice, and that utters nothing but a name, a name without an adjective, without a descriptive epithet for the person spoken to, such as is the rule in every Homeric address; and of Abraham too nothing is made perceptible except the words in which he answers God: Hinne-ni, Behold me here—with which, to be sure, a most touching gesture expressive of obedience and readiness is suggested, but it is left to the reader to visualize it. Moreover the two speakers are not on the same level: if we conceive of Abraham in the foreground, where it might be possible to picture him as prostrate or kneeling or bowing with outspread arms or gazing upward, God is not there too: Abraham’s words and gestures are directed toward the depths of the picture or upward, but in any case the undetermined, dark place from which the voice comes to him is not in the foreground.

'After this opening, God gives his command, and the story itself begins: everyone knows it; it unrolls with no episodes in a few independent sentences whose syntactical connection is of the most rudimentary sort. In this atmosphere it is unthinkable that an implement, a landscape through which the travelers passed, the servingmen, or the ass, should be described, that their origin or descent or material or appearance or usefulness should be set forth in terms of praise; they do not even admit an adjective: they are serving-men, ass, wood, and knife, and nothing else, without an epithet; they are there to serve the end which God has commanded; what in other respects they were, are, or will be, remains in darkness. A journey is made, because God has designated the place where the sacrifice is to be performed; but we are told nothing about the journey except that it took three days, and even that we are told in a mysterious way: Abraham and his followers rose “early in the morning” and “went unto” the place of which God had told him; on the third day he lifted up his eyes and saw the place from afar. That gesture is the only gesture, is indeed the only occurrence during the whole journey, of which we are told; and though its motivation lies in the fact that the place is elevated, its uniqueness still heightens the impression that the journey took place through a vacuum; it is as if, while he traveled on, Abraham had looked neither to the right nor to the left, had suppressed any sign of life in his followers and himself save only their footfalls.

'Thus the journey is like a silent progress through the indeterminate and the contingent, a holding of the breath, a process which has no present, which is inserted, like a blank duration, between what has passed and what lies ahead, and which yet is measured: three days! Three such days positively demand the symbolic interpretation which they later received. They began “early in the morning.” But at what time on the third day did Abraham lift up his eyes and see his goal? The text says nothing on the subject. Obviously not “late in the evening,” for it seems that there was still time enough to climb the mountain and make the sacrifice. So “early in the morning” is given, not as an indication of time, but for the sake of its ethical significance; it is intended to express the resolution, the promptness, the punctual obedience of the sorely tried Abraham. Bitter to him is the early morning in which he saddles his ass, calls his serving-men and his son Isaac, and sets out; but he obeys, he walks on until the third day, then lifts up his eyes and sees the place. Whence he comes, we do not know, but the goal is clearly stated: Jeruel in the land of Moriah. V/hat place this is meant to indicate is not clear—”Moriah” especially may be a later correction of some other word. But in any case the goal was given, and in any case it is a matter of some sacred spot which was to receive a particular consecration by being connected with Abraham's sacrifice. Just as little as “early in the morning” serves as a temporal indication does “Jeruel in the land of Moriah” serve as a geographical indication; and in both cases alike, the complementary indication is not given, for we know as little of the hour at which Abraham lifted up his eyes as we do of the place from which he set forth—Jeruel is significant not so much as the goal of an earthly journey, in its geographical relation to other places, as through its special election, through its relation to God, who designated it as the scene of the act, and therefore it must be named.'

I apologize for the length of this quote, but to me at least it does a good job of illustrating where Tolkien is also coming from in The Ainulindale and elsewhere when it comes to the "appearance" of Eru on stage in the story, and gives us something to think about as we move forward with the question of how to portray Eru and the Valar.

N. Trevor Brierly

New Member

1. I'm with those who argue against portraying Iluvatar at all. No matter what you do there will always be some who will think "No way Iluvatar, the One God, the creator of Arda, looks like that". That happens with any character portrayal of course. But more than any other character perhaps many of us will have our own idea of what Iluvatar might look like, and some of us will not have any idea at all and prefer to keep it that way. I know that I would probably find any depiction disappointing, because it collapses down all possibilities into an actuality, and I'd rather keep it at a multiplicity of possibilities in my own mind.

2. Concerning the Valar, on the other hand, I find myself feeling very differently. I've seen some very interesting and powerful images of the Valar and I think I would always enjoy seeing more. So I would be very interested to see the possibilities of we might portray them. I find myself attracted to the idea of animating them and the Ainulindalë, if it was well done. Something more like the non-goofy parts of Fantasia and Fantasia 2000.

2. Concerning the Valar, on the other hand, I find myself feeling very differently. I've seen some very interesting and powerful images of the Valar and I think I would always enjoy seeing more. So I would be very interested to see the possibilities of we might portray them. I find myself attracted to the idea of animating them and the Ainulindalë, if it was well done. Something more like the non-goofy parts of Fantasia and Fantasia 2000.

Trevor Trumbull

New Member

I think the idea of animating the Ainulindalë is an interesting once since it would afford us the chance to depict things that would be harder to do via a live action format. Yet having said that I agree with Nelson's point above about needing to settle on one format and stick with it, since switching from animation to live action or vise versa could be very jarring. As for which format that should be it seems to me that there are going to be many moments in the story: the coming of Fingolfin into Beleriand at the rising of the Moon, his fight with Morgoth, much of the Beren and Luthien and Turin stories, Hurin's "Day shall come again" moment to name just a handful of examples. that will need a lot of weight a lot of... gravitas to them. A gravitas that would be best achieved through live action.

The use of colour in the opening of the Ainulindalë is still a good idea. However, once again agreeing with Nelson, at some point at least the major Ainur are going to have to take on some sort of corporeal, or quasi corporeal, form. Once the conversations between Iluvatar and the Ainur, or amongst the Ainur, begin I think disembodied voices in abstract shapes or colours will be too much for people even those who have read the Ainulindalë many times and know what is happening.

The use of colour in the opening of the Ainulindalë is still a good idea. However, once again agreeing with Nelson, at some point at least the major Ainur are going to have to take on some sort of corporeal, or quasi corporeal, form. Once the conversations between Iluvatar and the Ainur, or amongst the Ainur, begin I think disembodied voices in abstract shapes or colours will be too much for people even those who have read the Ainulindalë many times and know what is happening.

Kim Moehle

New Member

This is one of those topics that could very likely set the tone of the test of the theoretical Silmfilm so I'm very glad we are addressing it right off the bat.

It's actually an issue that is cause for the most concern because the whole beginning sequences, Specifically the Ainlulindale, and Music of the Ainur, have the potential to come off as extremely hokey if not handled right.

While there are many ways to tackle this I'd like to suggest two things. In terms of tv episodes, I don’t know if the Music wold make for a fitting entire episode. Don’t get me wrong, I love the Ainlulindale and the first time I read it I literally had to stop and take some to really appreciate how beautiful the language is. Its gorgeous writing and the music it invokes makes me think of things out of this worls and awesome. But it may not be the best way to introduce your audience to the world and cast of characters.

As NicoleHobbitDay mentioned, this part does seem a bit like a prologue and could potentially be treated that way. i.e don’t begin the series with the Music but instead have that part of the story alluded to via flashback, references, a specific musical theme or visual clue. Potentially like in Harry Potter in the Deathly Hallows and Hermione is telling the story of the three brothers and it is told via gorgeous animation and voice over. That part really stuck with me because it was something that was radically different than what we had previously seen in the films and the form used to tell that story fit the tone of the content it as trying to convey.

Another suggestion would be to use the Music of the Ainur as a title sequence. There are some GORGEOUS title sequences out there (Game of Thrones, Blacksails, Daredevil, Vikings) that through music and images, really are able to convey the tone of the story that is about to be untold. Images of greco roman statues (not necessarily actual statues but images like that), empty orchestra pits, sheet music, light, fabrics, ect are some things that could be utilized.

While my comments have mostly been focused on the Music, I think it would be a good idea to have two differing depictions of the Valar, one pre / during the music and one post music once they have entered into Adra. I think post- entering into Arda we would certainly need to cast actors, but before that I'm all for animation or another means.

It's actually an issue that is cause for the most concern because the whole beginning sequences, Specifically the Ainlulindale, and Music of the Ainur, have the potential to come off as extremely hokey if not handled right.

While there are many ways to tackle this I'd like to suggest two things. In terms of tv episodes, I don’t know if the Music wold make for a fitting entire episode. Don’t get me wrong, I love the Ainlulindale and the first time I read it I literally had to stop and take some to really appreciate how beautiful the language is. Its gorgeous writing and the music it invokes makes me think of things out of this worls and awesome. But it may not be the best way to introduce your audience to the world and cast of characters.

As NicoleHobbitDay mentioned, this part does seem a bit like a prologue and could potentially be treated that way. i.e don’t begin the series with the Music but instead have that part of the story alluded to via flashback, references, a specific musical theme or visual clue. Potentially like in Harry Potter in the Deathly Hallows and Hermione is telling the story of the three brothers and it is told via gorgeous animation and voice over. That part really stuck with me because it was something that was radically different than what we had previously seen in the films and the form used to tell that story fit the tone of the content it as trying to convey.

Another suggestion would be to use the Music of the Ainur as a title sequence. There are some GORGEOUS title sequences out there (Game of Thrones, Blacksails, Daredevil, Vikings) that through music and images, really are able to convey the tone of the story that is about to be untold. Images of greco roman statues (not necessarily actual statues but images like that), empty orchestra pits, sheet music, light, fabrics, ect are some things that could be utilized.

While my comments have mostly been focused on the Music, I think it would be a good idea to have two differing depictions of the Valar, one pre / during the music and one post music once they have entered into Adra. I think post- entering into Arda we would certainly need to cast actors, but before that I'm all for animation or another means.

Steven Boettcher

New Member

I always pictured a scene similar to The Cottage of Lost Play where an Ælfwine like character hears the story from an elf and it would be in front of a fire and the flames would be animated to show the Music of the Ainur.

angeloftranshumanflesh

New Member

I didn't get to hear the episode live, but in my thinking none of the Ainulindale should be depicted. The whole Silmarillion takes the form of a "chain of reading" to borrow a phrase from Gergely Nagy, and I think that should be borne in mind.

It isn't a novel, or even a historical chronicle. Genre wise, it's "myth", akin to some real world works like the Titanomachia. Any adaptation should, I believe, reflect that. How? Well, have some character recount the Ainulindale perhaps. To literally show it is, I would submit, to misunderstand the text. It is written as a cosmogonic myth and it is a myth even within the world of the characters.

While the discussion here about animated vs live action is interesting I think it misses the point, slightly. In any case I'll listen the podcast and I'll be interested to hear what they think.

It isn't a novel, or even a historical chronicle. Genre wise, it's "myth", akin to some real world works like the Titanomachia. Any adaptation should, I believe, reflect that. How? Well, have some character recount the Ainulindale perhaps. To literally show it is, I would submit, to misunderstand the text. It is written as a cosmogonic myth and it is a myth even within the world of the characters.

While the discussion here about animated vs live action is interesting I think it misses the point, slightly. In any case I'll listen the podcast and I'll be interested to hear what they think.

Bre

Active Member

Okay, I’m going to post my promised bit about visualization of the Valar, and then I’m going to reply to all the awesome ideas people have brought up (it’s cool how many people have commented already)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

First, Valar depictions. I think it’s safe to assume that we’re all basically saying the same thing: that Valar at first don’t have corporeal/concrete forms but will evolve and change their forms as the story progresses into some pretty rad character designs. The controversy of will we/won’t we show them lies in their non-corporeal appearance, but once they take on physical forms and descend into Arda, that’s where the controversy ends and we all can just have fun suggesting cool character design ideas.

As I see it, there are few distinct periods of time, which each would herald in a new design for each Valar

I drew up some quick Yavanna sketches to show an example of how a design for one of the Valar might stay similar but change over time from more mythic to anthropomorphic (I assume they’d take on these more humanoid forms to make the elves feel more comfortable).

Note: These drawings are the first time I’ve ever drawn Yavanna, and I already have changed my mind about most of the decisions I made, but I don’t have time to make additional design passes right now.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Now for comments on other posts:

Firstly, I agree with everyone who has proposed that the hypothetical Silmarillion film use a large library of leitmotifs and themes assigned to various characters and ideas to create a more cohesive narrative through the score alone. The Lord of the Rings films did this extremely well

(there’s actually a cool book that collects and breaks them all down by Doug Adams called ‘The Music of the Lord of the Rings Films’ if anyone is interested), and it’s a high-bar that we should also strive to improve upon. Obviously the actually Ainulindale orchestral piece has to be this great amazing thing all on it’s own, but themes present in it would naturally reemerge at decisive points in other stories later on down the line to create certain thematic connections.

When I imagine what Melkor’s discord sounds like I hear nothing but a sudden bombardment of brass XD.

As for vocals, voices singing the story, as in clearly just telling the audience what’s going on in song is off-putting to me (not that you were suggesting that). However, that doesn’t meant there couldn’t be a choir at play in the Ainulindale music piece; in fact, there probably would and should.

Voices could be used as instruments, and the language could just be Sindarin or Quenya, so while we could be nerds and translate it later, the importance of said choir would just be to help back up the emotional tone of a narrative point in the music and help distinguish individual musical characters. For instance, the choir associated with the discord of Melkor would probably have more masculine and baritone vocalists, whereas the singers associated with the third theme/Nienna/men could be younger more sorrowful voices or just something that sounds like Renee Fleming during ‘The Eagles’ from the extended OST for Return of the King.

I wanted to reference Evan Palmer’s comic in my first post, but I couldn’t remember that he was the one who drew it. Yes. Thanks! It is a very good start in terms of visually conceptualizing a direction to go in.

I seem to have caused somewhat of a stir with my animated Silmarillion suggestion, haha.

HOWEVER, I want to make something very clear: when I say that the Ainulindale must be animated regardless of whether or not the rest of the film is animated or live-action, I am not saying that it must be 2d animated no matter what. What I am saying is that if the whole adaptation The Silmarillion ends up being live-action, the Ainulindale isn’t something you can really film, and most of it would be CGI anyways, and CGI is animation, even if that animation is stylized to look like live-action.

But Holmes, while I think it’s okay for one one person to prefer a live-action Silmarillion while another prefers an animated version, I do not agree with the above reasoning that animation is the easier adaption rode to take or that it is less believable. I will admit that being an animator myself that I am extremely biased on this subject, but animation is hard and has its own set of adaption obstacles to overcome just like a live-action; it is not the easy road out. Yes, I think some ideas and concepts are could be better communicated through an animated version as opposed to a live-action one, but only in the sense that they’re not as common in live-action. If I personally was forced to make a live-action version of The Silmarillion, I wouldn’t care if these visual techniques were traditionally only employed in animation and would do them in live-action anyways; the only difficulty is that there is less of a precedent in live-action to date.

As for believability, I find animation in it’s highest form, to be more believable than live-action, but I recognize that this is just my personal opinion and will differ from individual to individual. Believability isn’t about whether or not something looks like real-life in the sense of being depicted as a three-dimensional and realistically-lite world, it’s about whether or not the story and concepts being presented are coherent and do not break the illusion of a created secondary world.

When it comes to live-action vs animation, it is simply an aesthetic preference. If you prefer live-action that’s cool (I like seeing fan-made interpretations in multiple styles and mediums), but don’t say one is a visually superior medium to the other when they both have their own merits and flaws. I think animation probably comes off as lesser or distasteful to some because they think of Disney films, but there are plenty of other styles of animation, and I am certainly am not picturing the Silmarillion in a Disney style.

In the end, I don’t think deciding on whether the film should or should not be animated is particularly important since I don’t think it really changes anything in terms of future discussions; it's going to be pretty much impossible for anyone to agree on a visual style anyways, especially through an audio podcast.

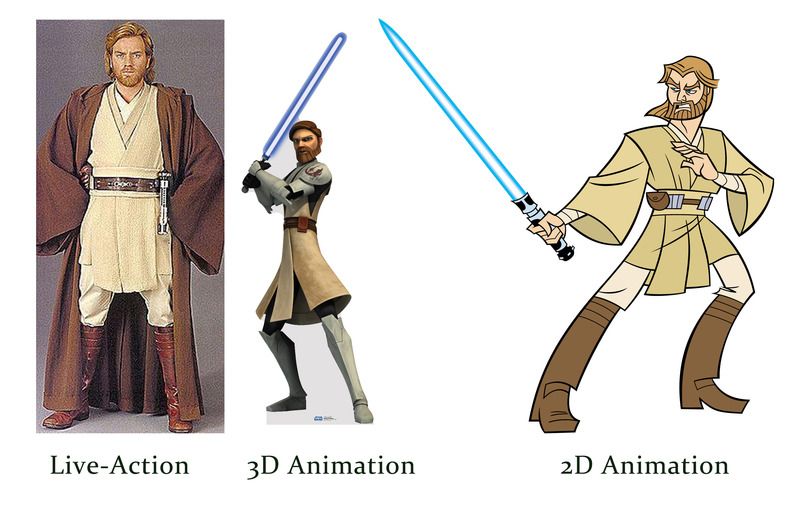

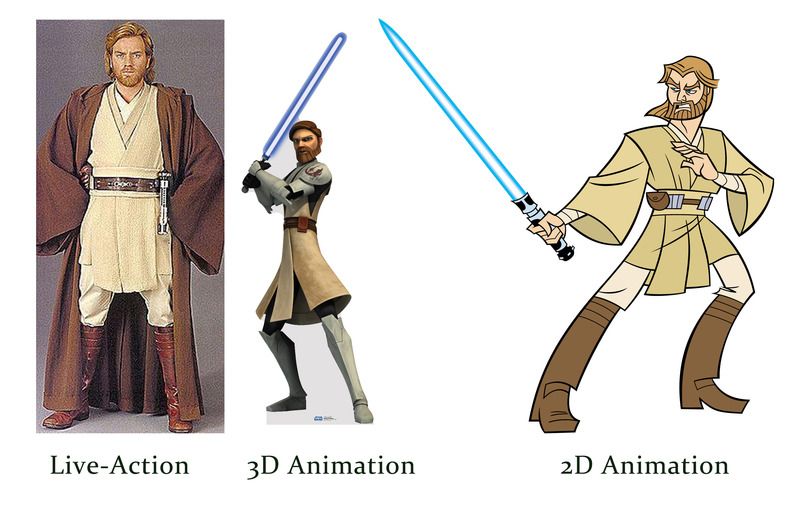

I mean you could talk about Obi-wan from the Star Wars prequels and all agree on the basic design and character, but all be imagining something different:

In any case, I expect the show hosts to go in a live-action direction anyways, and the only time for animation to really come up would be when deciding if a character would be CGI or something (like Golumn).

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

First, Valar depictions. I think it’s safe to assume that we’re all basically saying the same thing: that Valar at first don’t have corporeal/concrete forms but will evolve and change their forms as the story progresses into some pretty rad character designs. The controversy of will we/won’t we show them lies in their non-corporeal appearance, but once they take on physical forms and descend into Arda, that’s where the controversy ends and we all can just have fun suggesting cool character design ideas.

As I see it, there are few distinct periods of time, which each would herald in a new design for each Valar

- Ainulindale (non-corporeal)

- Descent in Arda (first corporeal bodies)

- Post-destruction of the Two Lamps (first transition stage from elemental to anthropomorphic)

- Awakening of the Elves

- Flight of the Nolodor

- War of Wrath

I drew up some quick Yavanna sketches to show an example of how a design for one of the Valar might stay similar but change over time from more mythic to anthropomorphic (I assume they’d take on these more humanoid forms to make the elves feel more comfortable).

Note: These drawings are the first time I’ve ever drawn Yavanna, and I already have changed my mind about most of the decisions I made, but I don’t have time to make additional design passes right now.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Now for comments on other posts:

Firstly, I agree with everyone who has proposed that the hypothetical Silmarillion film use a large library of leitmotifs and themes assigned to various characters and ideas to create a more cohesive narrative through the score alone. The Lord of the Rings films did this extremely well

(there’s actually a cool book that collects and breaks them all down by Doug Adams called ‘The Music of the Lord of the Rings Films’ if anyone is interested), and it’s a high-bar that we should also strive to improve upon. Obviously the actually Ainulindale orchestral piece has to be this great amazing thing all on it’s own, but themes present in it would naturally reemerge at decisive points in other stories later on down the line to create certain thematic connections.

Using classical pieces, however, would be difficult when we arrive at Melkor's discord and the harmony Iluvatar brings out of it. I like the idea of the music being instrumental rather than vocal, for the Valar specifically, because it would add to the difference between the Valar and the children of Iluvatar.

When I imagine what Melkor’s discord sounds like I hear nothing but a sudden bombardment of brass XD.

As for vocals, voices singing the story, as in clearly just telling the audience what’s going on in song is off-putting to me (not that you were suggesting that). However, that doesn’t meant there couldn’t be a choir at play in the Ainulindale music piece; in fact, there probably would and should.

Voices could be used as instruments, and the language could just be Sindarin or Quenya, so while we could be nerds and translate it later, the importance of said choir would just be to help back up the emotional tone of a narrative point in the music and help distinguish individual musical characters. For instance, the choir associated with the discord of Melkor would probably have more masculine and baritone vocalists, whereas the singers associated with the third theme/Nienna/men could be younger more sorrowful voices or just something that sounds like Renee Fleming during ‘The Eagles’ from the extended OST for Return of the King.

I agree with the others that say the Ainulindale needs to be animated. I think we could take Evan Palmer's take on it as a good inspiration for what the visuals might look like. I think that none of the Ainur or Iluvatar would actually have dialog - it would all be narration by someone in the frame narrative..

I wanted to reference Evan Palmer’s comic in my first post, but I couldn’t remember that he was the one who drew it. Yes. Thanks! It is a very good start in terms of visually conceptualizing a direction to go in.

I disagree with all proposals that The Silmarillion be animated, for three primary reasons.

1. It would certainly work from a practical standpoint, but I think it robs us of some great challenges. It feels like a shortcut that allows us to gloss over things that would be "too difficult" to portray onscreen via live action, VFX , or CGI. Animation gives us a way to skirt around some of the real difficulties of adapting The Silmarillion for the screen and making it believable. The beauty of animation is that it doesn't have to be believable, but the tragedy therein is that it cannot, by its very nature, be believable (but more on that later). My primary point here is that trying to envision The Silmarillion as a live action series is hard, perhaps even impossible in some places, but such is the nature of adaptation. It is our job, as the adapters, to figure out how to make it work. Animation might relieve us of a few of those hard choices, but that's half the fun of working out a good adaptation!

I seem to have caused somewhat of a stir with my animated Silmarillion suggestion, haha.

HOWEVER, I want to make something very clear: when I say that the Ainulindale must be animated regardless of whether or not the rest of the film is animated or live-action, I am not saying that it must be 2d animated no matter what. What I am saying is that if the whole adaptation The Silmarillion ends up being live-action, the Ainulindale isn’t something you can really film, and most of it would be CGI anyways, and CGI is animation, even if that animation is stylized to look like live-action.

But Holmes, while I think it’s okay for one one person to prefer a live-action Silmarillion while another prefers an animated version, I do not agree with the above reasoning that animation is the easier adaption rode to take or that it is less believable. I will admit that being an animator myself that I am extremely biased on this subject, but animation is hard and has its own set of adaption obstacles to overcome just like a live-action; it is not the easy road out. Yes, I think some ideas and concepts are could be better communicated through an animated version as opposed to a live-action one, but only in the sense that they’re not as common in live-action. If I personally was forced to make a live-action version of The Silmarillion, I wouldn’t care if these visual techniques were traditionally only employed in animation and would do them in live-action anyways; the only difficulty is that there is less of a precedent in live-action to date.

As for believability, I find animation in it’s highest form, to be more believable than live-action, but I recognize that this is just my personal opinion and will differ from individual to individual. Believability isn’t about whether or not something looks like real-life in the sense of being depicted as a three-dimensional and realistically-lite world, it’s about whether or not the story and concepts being presented are coherent and do not break the illusion of a created secondary world.

When it comes to live-action vs animation, it is simply an aesthetic preference. If you prefer live-action that’s cool (I like seeing fan-made interpretations in multiple styles and mediums), but don’t say one is a visually superior medium to the other when they both have their own merits and flaws. I think animation probably comes off as lesser or distasteful to some because they think of Disney films, but there are plenty of other styles of animation, and I am certainly am not picturing the Silmarillion in a Disney style.

In the end, I don’t think deciding on whether the film should or should not be animated is particularly important since I don’t think it really changes anything in terms of future discussions; it's going to be pretty much impossible for anyone to agree on a visual style anyways, especially through an audio podcast.

I mean you could talk about Obi-wan from the Star Wars prequels and all agree on the basic design and character, but all be imagining something different:

In any case, I expect the show hosts to go in a live-action direction anyways, and the only time for animation to really come up would be when deciding if a character would be CGI or something (like Golumn).

Trevor Trumbull

New Member

I didn't get to hear the episode live, but in my thinking none of the Ainulindale should be depicted. The whole Silmarillion takes the form of a "chain of reading" to borrow a phrase from Gergely Nagy, and I think that should be borne in mind.

It isn't a novel, or even a historical chronicle. Genre wise, it's "myth", akin to some real world works like the Titanomachia. Any adaptation should, I believe, reflect that. How? Well, have some character recount the Ainulindale perhaps. To literally show it is, I would submit, to misunderstand the text. It is written as a cosmogonic myth and it is a myth even within the world of the characters.

While the discussion here about animated vs live action is interesting I think it misses the point, slightly. In any case I'll listen the podcast and I'll be interested to hear what they think.

How are you defining myth? Using the OED's definitions do you mean "a widespread but untrue or erroneous story or belief; a widely held misconception"? Or rather "a traditional story, typically involving supernatural beings or forces, which embodies and provides an explanation, aetiology, or justification for something such as the early history of a society, a religious belief or ritual, or a natural phenomenon"? There are some mythic elements, and there I am using the second definition, but we have to be careful of labeling the whole thing as myth. I think we can say with near certainty that the Silmarillion is Bilbo's translations from the elvish that he wrote while in Rivendell. In essence then he would have heard the stories from elves who would have life through the events, or else who would have learned of them from those who had. In the case of Creation the elves would have learned of it from the Valar who were there.